10 January 2005Thom Hartmann

The Gonzales confirmation is not just about the torture memos. It's much bigger than that.

If Bush continues to roll back human and civil rights - and the installation of Alberto Gonzalez as America's chief law enforcement officer is very much a part of his campaign to do so - we may be facing a "Pastor Niemöller moment" sooner than most of us could have imagined.

Tuesday, January 10, 2005, is the third anniversary of the opening of America's first concentration camp since Japanese Americans were shamefully interred during WWII. Since the first Guantanamo camp was opened, the Bush administration has built additional concentration camps - the latest known as Camp Five - in Cuba, and is asking Congress for $29 million to build concentration Camp Six.

These concentration camps detain uncharged, untried, unconvicted individuals, who may be held for the rest of their lives because, as the UK's Guardian newspaper noted on January 5th of this year, the Bush administration "lacks proof" that they are either criminals or POWs.

This is one of the more visible parts of a much larger campaign the Bush administration has embarked on to reverse not only 229 years of the American rule of law regarding the rights of average citizens, but nearly eight centuries of human rights that go back to an epic moment in 1215 on a meadow by the River Thames.

The modern institution of civil and human rights, and particularly the writ of habeas corpus, began in June of 1215 when King John was forced by the feudal lords to sign the Magna Carta at Runnymede. Although that document mostly protected "freemen" - what were then known as feudal lords or barons, and today known as CEOs and millionaires - rather than the average person, it initiated a series of events that echo to this day.

Two of the most critical parts of the Magna Carta were articles 38 and 39, which established the foundation for what is now known as "habeas corpus" laws (literally, "produce the body" from the Latin - meaning, broadly, "let this person go free"), as well as the Fourth through Eighth Amendments of our Constitution and hundreds of other federal and state due process provisions.

Articles 38 and 39 of the Magna Carta said:

"38 In future no official shall place a man on trial upon his own unsupported statement, without producing credible witnesses to the truth of it.

"39 No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land."

This was radical stuff, and over the next four hundred years average people increasingly wanted for themselves these same protections from the abuse of the power of government or great wealth. But from 1215 to 1628, outside of the privileges enjoyed by the feudal lords, the average person could be arrested and imprisoned at the whim of the king with no recourse to the courts.

Then, in 1627, King Charles I overstepped, and the people snapped. Charles I threw into jail five knights in a tax disagreement, and the knights sued the King, asserting their habeas corpus right to be free or on bail unless convicted of a crime.

King Charles I, in response, invoked his right to simply imprison anybody he wanted (other than the rich), anytime he wanted, as he said, "per speciale Mandatum Domini Regis."

This is essentially the same argument that George W. Bush makes today for why he has the right to detain both citizens and non-citizens solely on his own say-so: because he's in charge. And it's an argument supported by Alberto Gonzales.

But just as George's decree is meeting resistance, Charles' decree wasn't well received. The result of his overt assault on the rights of citizens led to a sort of revolt in the British Parliament, producing the 1628 "Petition of Right" law, an early version of our Fourth through Eighth Amendments, which restated Articles 38 and 39 of the Magna Carta and added that "writs of habeas corpus, [are] there to undergo and receive [only] as the court should order." It was later strengthened with the "Habeas Corpus Act of 1640" and a second "Habeas Corpus Act of 1679."

Thus, the right to suspend habeas corpus no longer was held by the King. It was exercised solely by the people's (elected and hereditary) representatives in the Parliament.

The third George to govern the United Kingdom confronted this in 1815 when he came into possession of Napoleon Bonaparte. But the British laws were so explicit that everybody was entitled to habeas corpus - even people who were not British citizens - that when Napoleon surrendered on the deck of the British flagship Bellerophon after the battle of Waterloo in 1815, the British Parliament had to pass a law ("An Act For The More Effectually Detaining In Custody Napoleon Bonaparte") to suspend habeas corpus so King George III could legally continue to hold him prisoner (and then legally exile him to a British fortification on a distant island).

Ironically, the third George to govern the United States now says, 190 years later, that unlike England's George III, he does not need an act of Congress to detain people or exile them to camps on a distant island.

To facilitate this, our Third George, and his able counselor Judge Gonzales, have brought forth new "legal" terms - "enemy combatant" and "terrorist" - and invented a new set of law and rights (or non-laws and non-rights) for people they label as such.

It's a virtual repeat of Charles I's doctrine that a nation's ruler may do whatever he wants because he's the one in charge - "per speciale Mandatum Domini Regis."

Interestingly, the United States Constitution does provide for special exceptions to the involuntary detention of persons - it is legal to suspend habeas corpus. But the Constitution says it can only be done by Congress, not by the President.

Article I of the Constitution outlines the powers and limits of the Legislative Branch of government (Article 2 lays out the Executive Branch, and Article 3 defines the Judicial Branch). In Section 9, Clause 2 of Article I, the Constitution says of the Legislative branch's authority: "The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it."

Abraham Lincoln was well aware of this during the Civil War, and was the first president to successfully ask Congress (on March 3, 1863) to suspend habeas corpus so he could imprison those he considered a threat until the war was over. Congress invoked this power again during Reconstruction when President Grant requested The Ku Klux Klan Act in 1871 to put down a rebellion in South Carolina.

But President George W. Bush has not asked Congress for, and has not been granted, a suspension of habeas corpus for his so-called "war on terrorism," a "war" which he and his advisors have implied may last well beyond our lifetimes.

Nonetheless, our President, with consent of his Counsel Mr. Gonzales, has locked people up, "per speciale Mandatum Domini Regis." Some of their names are familiar to us - US citizens Jose Padilla and Yaser Hamdi, for example - but there are hundreds whose names we are not even allowed to know. Perhaps thousands. It's a state secret, after all. Per speciale Mandatum Domini Regis.

But how do we deal with people who want to kill us, to destroy our nation, to terrorize us?

Every president from George Washington to Bill Clinton has understood that there are two categories of people who can be incarcerated legally - Prisoners of War and criminals. The former have rights under both U.S. law and the Geneva Conventions, and the latter under the U.S. Constitution.

These two categories encompass every possible actual threat to a nation and its people, and have withstood the test of time from the days of King John to today.

For example, when Bill Clinton was confronted with a heinous act of terrorism within the United States - the bombing of the Federal Building in Oklahoma City - he didn't declare a "war" on whoever the terrorist may be, or suspend habeas corpus. Instead, he immediately defined the perpetrators as thugs and criminals, and brought the full weight of the American and international criminal justice system to bear, capturing Timothy McVeigh and using Interpol to search the world for possible McVeigh allies. Justice was served, the victims achieved closure, and our rights were left largely intact.

But, just as Hitler and his close advisors used the burning of the Reichstag building to declare a perpetual "war on terrorism," and then moved to suspend habeas corpus and other rights, so too have George W. Bush and Alberto Gonzales.

The Founders must be turning in their graves. Clearly they never imagined such a thing in their wildest dreams. As Alexander Hamilton - arguably the most conservative of the Founders - wrote in Federalist 84:

"The establishment of the writ of habeas corpus ... are perhaps greater securities to liberty and republicanism than any it [the Constitution] contains. ...[T]he practice of arbitrary imprisonments have been, in all ages, the favorite and most formidable instruments of tyranny. The observations of the judicious [British 18th century legal scholar] Blackstone, in reference to the latter, are well worthy of recital:

"'To bereave a man of life,' says he, 'or by violence to confiscate his estate, without accusation or trial, would be so gross and notorious an act of despotism, as must at once convey the alarm of tyranny throughout the whole nation; but confinement of the person, by secretly hurrying him to jail, where his sufferings are unknown or forgotten, is a less public, a less striking, and therefore A MORE DANGEROUS ENGINE of arbitrary government.''' [Capitals all Hamilton's from the original.]

While the sexy stuff that members of Congress and the news media want to talk about when they question Alberto Gonzales is torture - after all, the pictures are now iconic and have worldwide distribution - the torture of these and other prisoners in US custody is really a subset of a larger issue.

The bigger question here is whether George W. Bush has the right to ignore the U.S. Constitution and international treaties, violate human rights and civil liberties, promote "preemptive" wars, and build concentration camps for the permanent imprisonment of untried and unconvicted individuals - all simply because he says he can, per speciale Mandatum Domini Regis. And whether we want the chief law enforcement officer of the land, the man who would be charged with prosecuting Bush or those in his administration who may break the law, to be a man who agrees that Bush stands above the law and the Constitution.

The question, ultimately, is whether our nation will continue to stand for the values upon which it was founded.

Early American conservatives suggested that democracy was so ultimately weak it couldn't withstand the assault of newspaper editors and citizens who spoke out against it, or terrorists from the Islamic Barbary Coast, leading John Adams to pass America's first PATRIOT Act-like laws, the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. President Thomas Jefferson rebuked those who wanted America ruled by an iron-handed presidency that could - as Adams had - throw people in jail for "crimes" such as speaking political opinion, or without constitutional due process.

"I know, indeed," Jefferson said in his first inaugural address on March 4, 1801, "that some honest men fear that a republican government cannot be strong; that this government is not strong enough.

"But would the honest patriot,"he continued, "in the full tide of successful experiment, abandon a government which has so far kept us free and firm, on the theoretic and visionary fear that this government, the world's best hope, may by possibility want energy to preserve itself? I trust not.

"I believe this, on the contrary, the strongest government on earth. I believe it is the only one where every man, at the call of the laws, would fly to the standard of the law, and would meet invasions of the public order as his own personal concern."

The sum of this, Jefferson said, was found in "freedom of person under the protection of the habeas corpus; and trial by juries impartially selected. These principles form the bright constellation which has gone before us, and guided our steps through an age of revolution and reformation.

"The wisdom of our sages and the blood of our heroes have been devoted to their attainment. They should be the creed of our political faith, the text of civil instruction, the touchstone by which to try the services of those we trust; and should we wander from them in moments of error or alarm, let us hasten to retrace our steps and to regain the road which alone leads to peace, liberty, and safety."

Modern conservatives still revere Burke and Adams and sneer at Jefferson, but many are nonetheless alarmed by Bush's unprecedented attack on the Constitution. As Russell Kirk wrote in his seminal 1953 book "The Conservative Mind" - the book which inspired a generation of conservatives from Buckley to Goldwater - a "New Society," abandoning the traditional values of America, could easily come into being if "radicals" such as Bush were to take over our government and discard the Constitution.

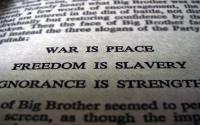

This New Society, Kirk wrote in his chapter "The Promise of Conservatism," would be dominated by "the gratification of a lust for power and the destruction of all ancient political institutions in the interest of the new dominant elites. The great Plan requires that the public be kept constantly in an emotional state closely resembling that of a nation at war; this lacking, obedience and co-operation shrivel..." Kirk adds that "Big Brother remains to show the donkey the stick instead of the carrot."

When I was working in Russia some years ago, a friend in Kaliningrad told me a perhaps apocryphal story about Nikita Khrushchev, who, following Stalin's death, gave a speech to the Politburo denouncing Stalin's policies. A few minutes into Khrushchev's diatribe, somebody shouted out, "Why didn't you challenge him then, the way you are now?"

The room fell silent, as Khrushchev angrily swept the audience with his glare. "Who said that?" he asked in a reasoned voice. Silence.

"Who said that?" Khrushchev demanded, leaning forward. Silence.

Pounding his fist on the podium to accent each word, he screamed, "Who - said - that?" Still no answer.

Finally, after a long and strained silence, the elected politicians in the room fearful to even cough, a corner of Khrushchev's mouth lifted into a smile.

"Now you know," he said with a chuckle, "why I did not speak up against Stalin when I sat where you now sit."

The question for our day is who will speak up against George W. Bush and his Stalinist policies? Who will speak against the man who punishes reporters and news organizations by cutting off their access; who punishes politicians by targeting them in their home districts; who punishes truth-tellers in the Executive branch by character assassination that even extends to destroying their spouse's careers?

Oddly, so far it's only been Justice Antonin Scalia, a man with whom I often strongly disagree. Scalia wrote in his minority dissent in the case of Hamdi v. Rumsfeld that the President does not have the power to suspend habeas corpus by executive decree. Instead, he wrote: "If civil rights are to be curtailed during wartime, it must be done openly and democratically, as the Constitution requires..."

Scalia went on to quote Alexander Hamilton from Federalist Number 8, who noted that:

"The violent destruction of life and property incident to war; the continual effort and alarm attendant on a state of continual danger, will compel nations the most attached to liberty, to resort for repose and security to institutions which have a tendency to destroy their civil and political rights. To be more safe, they, at length, become willing to run the risk of being less free."

"The Founders warned us about the risk," Scalia noted in his Hamdi dissent, "and equipped us with a Constitution designed to deal with it.

"Many think it not only inevitable but entirely proper that liberty give way to security in times of national crisis..." but, Scalia added, "that view has no place in the interpretation and application of a Constitution designed precisely to confront war and, in a manner that accords with democratic principles, to accommodate it."

How ironic that Justice Scalia was willing to stand up to George W. Bush and Alberto Gonzales, but most of the Senate Democrats won't.

The Democrats in Congress say they're going to confirm Judge Gonzales and "keep their powder dry" for future, larger battles like Supreme Court nominations. But as Pastor Niemöller reminds us, the loss of liberty is incremental, not sudden and dramatic.

One either totally stands for republican democracy, the Constitution, and the rule of law in our republic, or one doesn't. Gonzales has shown that he does not, both by his prevarication in his confirmation hearings, his actions in condoning Bush's illegal suspension of habeas corpus and PATRIOT Act abuses of constitutionally-protected civil and human rights, and his support of other Bush decrees implicitly per speciale Mandatum Domini Regis.

To quote Scalia's summary in the Hamdi case, "Because the Court has proceeded to meet the current emergency in a manner the Constitution does not envision [by letting the President suspend habeas corpus], I respectfully dissent."

But is dissent enough?

Or must we work for a wholesale change in our representatives, demanding that they either stand up for the principles for which so many Americans have fought and died, or leave the political arena altogether?

Where are the true democrats among the Democrats? (Or, for that matter, the true republicans among the Republicans?) Have they all lost their voices?

First Bush and Gonzales came for the terrorists, but I was not a terrorist, so I did not speak out. Then they came for the enemy combatants, but I was not a combatant, so I did not object. Then they came for the protestors resisting "free speech zones" near Bush campaign rallies, but I was not a protestor and so I only voiced my unease.

If we - and our elected representatives - do not speak out now, loudly and forcefully, it may not be long before they come for the rest of us.

Thom Hartmann [thom (at) thomhartmann.com] is a Project Censored Award-winning best-selling author and host of a nationally syndicated daily progressive talk show. www.thomhartmann.com His most recent books include "The Last Hours of Ancient Sunlight," "The Prophet's Way," "Unequal Protection," "We The People," "The Edison Gene", and "What Would Jefferson Do?."