13 November 2006

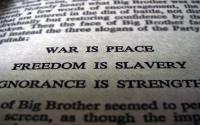

The huge man-made desert is a vivid reminder of the damage emissions can make |

Here, in the heart of the Kola peninsula, the destruction stretches across an area so great it has been described as perhaps the largest man-made desert in the world.

"There used to be big forests here," observes Sergei Zhavoronkin, director of local green group Bellona. "We are concerned about the future."

Yet, what looks like scorched earth is not the result of a vast, uncontrollable fire ravaging Europe's most ancient forests.

This is a direct and predictable result of decades of nickel, cobalt and copper smelting in the nearby town Monchegorsk.

Yet, on arrival in the town there are no visible signs of pollution.

"The microclimate is unique here," observes Mr Zhavoronkin, explaining how the smelting plant's location was carefully chosen following studies of prevailing wind directions.

"This is why there are many trees in the town, yet all the forests between the factories and the mountain range have been wiped out."

Improved standards

Monchegorsk is, along with fellow company towns Nikel and Zapolyarny further north, one of Russia's most polluted areas.

|

But, for the people living in this arctic company town, life has improved measurably in recent years.

Although sulphur dioxide emission levels remain high, they have fallen to about one sixth of the levels seen in the early 1990s.

And "better technology for controlling emissions... should ensure that these emissions continue to decrease", according to the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme's Arctic Pollution 2006 report.

In addition, people here have gained from a global metals boom. Nickel prices have more than doubled this year to trade at record highs over $30,000 (£15,742) a tonne.

This has helped spark a sharp rise in net profits for MMC Norilsk Nickel -Russia's largest privately-owned mining and metallurgical company - to $2.4bn for the six months to June, up from about $1bn during the same period last year.

In Monchegorsk it is obvious that the company has ploughed back much of the proceeds to raise living standards for its workers.

The roads are in good condition, the buildings have recently been renovated, and at the end of the main road lies Lake Imandra, a stark reminder of how Monchegorsk, or "beautiful tundra", earned its name.

Russia's Klondike

Norilsk Nickel is keen to stress the benefits of the metals boom, given that "on the Kola Peninsula... the lives and livelihoods of the population are entirely dependent on the development of heavy industry".

Yet, strong global metals markets mean environmentalists remain concerned.

As the extraction of the seemingly endless tundra's hidden wealth of mineral reserves has become increasingly lucrative, fresh plans for a massive expansion in mining and smelting operations by giant companies has emerged.

Already, most of the shipments through Murmansk's Barents Sea port to the north or Kandalaksha's White Sea port to the south is made up of metals and minerals, and the bulk is set to grow.

Norilsk Nickel, which supplies the car industry with palladium, platinum and rhodium, is looking to expand its operations.

The Russian steel and mining giant Severstal has linked up with South Africa's Anglo-American to jointly explore Kola deposits of zinc, copper and nickel.

And fertiliser-maker Akron is preparing to develop apatite fields in the Khibini mountains, an area used for reindeer grazing above the salmon-rich river system that runs south from Lake Imandra.

Apatite, a phosphate, is a key raw material of some fertilisers.

"We live on the Kola peninsula and like others in the Northern territories there is plenty more resources in the area," says Mr Zhavoronkin.

"But we'll need to minimise the impact on the environment, since more mining activity will cause more lakes and rivers to vanish."

Human suffering

It is hard to exaggerate the fragility of the arctic environment.

And the environmental degradation does more than just leave a visible impact.

On the Kola peninsula, authorities say the levels of iron and chemicals in the drinking water is too high, and Monchegorsk is among the places where the quality is the worst.

In addition, many of those working in the mines and processing plants suffer from ill health, ranging from throat irritation to cardio-respiratory disease and cancer.

Although not scientifically proven, many suspect it is caused by emissions, or by the inhalation of dust and particles in the workplace.

Beyond the workplace, however, "studies have not found any significant effects on human health", according to the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme.

Hence, although ill health is widespread, it "seems more related to socio-economic conditions than to environmental pollution".