16 November 2006Clayton Sandell and Bill Blakemore

"Choosing shorts or long underwear on a particular day is about weather; the ratio of shorts to long underwear in the drawer is about climate."

-- Charles Wohlforth, "The Whale and the Supercomputer"

You probably noticed there were fewer Atlantic hurricanes this year. Melting Arctic sea ice came extremely close to but didn't break the record minimum of summer 2005. And today, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, announced two months of cooler-than-average temperatures across the United States.

So what happened to global warming?

Scientists who study climate say they get that question every time there's a cold spell. Their answer: It's important to keep in mind an important concept.

Weather is not climate.

Weather, as we all know, is what we see in the day-to-day, often unpredictable fluctuations in local temperature, humidity, precipitation and wind.

"The fact that we had a couple of cool months doesn't say anything at all about long-term trends," said Mark Serreze, a research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center. "It's just a clear example of natural variability on the climate system. The long-term averages are decidedly toward a warming planet."

Kevin Trenberth, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, agreed.

"Weather is chaotic. It has an infinite amount of variability, and that's just the nature of weather," he said. "Weather dominates on a day-to-day basis, and there will be warmer period and cooler periods. But it's the overall pattern that gives you the climate."

And that, said climate scientists, means the occasional cold snap is not inconsistent with global warming, just as a heat wave may not by itself indicate global warming.

Temperatures

Long-term trends in the data tell scientists that the planet is getting warmer. Weather events that suggest otherwise are to be expected, they said.

"We have a gradual warming of Earth's system, but that is interspersed with a strong natural variability in the system," Serreze said. "This is just the way the system works."

Scientists also note that the five-warmest annual temperatures in the last century have all occurred in the last eight years. NOAA said today that globally, temperatures for October are well above average, and the month was the fourth warmest on record.

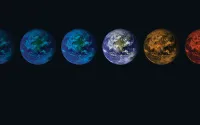

The average global temperature has risen by about one degree Fahrenheit over the past century. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which represents hundreds of scientists studying climate change in the United States and worldwide, predicted future temperature increases this century of anywhere from two degrees to eight degrees.

Hurricanes

Short-term variability also helps explain the dramatic difference between recent hurricane seasons.

In 2005, for example, there were a record 27 named storms during the North Atlantic hurricane season, including Katrina, Rita and Wilma. The 2006 season, while an average season, was much quieter, and no storms hit the U.S. coast.

The Pacific, on the other hand, has seen an intense hurricane season.

Typhoon Saomai, a Category 4 storm with sustained winds up to 150 miles per hour, drove half a million Chinese inland, caused massive flooding, and left 900 fishing boats lost at sea. No one knows how many people were killed.

Hurricane Sergio, which is not threatening land, is currently churning across the Pacific and is the 19th named storm of the season.

Chalk it up to natural fluctuations in weather patterns, said Trenberth. In this case, the cause is the periodic warming and cooling cycles in the Pacific Ocean known as El Niño and La Niña.

In the winter of 2004-2005, warmer water temperatures brought on by a weak El Niño meant lighter winds and sunny skies in the tropical Atlantic, where hurricanes form.

"The sun was beating down.There was less heat energy being sucked out by trade winds," said Trenberth. "The water warmed up and that set the stage for the 2005 season."

But this season the opposite occurred. A La Niña cooling of the Pacific Ocean led to stronger trade winds that pulled more heat energy out of the ocean while also helping prevent hurricane-strength winds from forming. Cloudier skies meant the sun didn't heat the oceans as much.

"There was very little heat in the ocean" compared with 2005, Trenberth said.

Despite the natural fluctuations, a growing body of scientific research argues that human-induced global warming is having an increasing effect on the intensity of hurricanes.

Scientists said it is difficult to predict just how future hurricane seasons will stack up, but according to a 2005 study by scientists at Georgia Tech University and the National Center for Atmospheric Research, the number of Category 4 and 5 hurricanes -- packing winds up to 155 miles an hour -- has doubled in the past 35 years.

Ice

Up in the Arctic, the amount of summer sea ice that melted in the summer of 2006 may not have broken the record set in 2005, but that doesn't necessarily mean good news, Serreze said.

Throughout the early summer, for example, the amount of sea ice was well below the 2005 record. An unusually cooler, cloudy August that reflected the sun's energy away from the ice helped reverse the steady downward trend.

The big picture, researchers said, shows that Arctic sea ice is "sharply declining" and has melted back at almost 10 percent per decade over the last 30 years. If that trend continues, some scientists believe the Arctic could be completely ice free by 2060.

"In terms of the long-term trends in the Arctic sea ice cover, I'm certainly pessimistic," Serreze said.

We'll still need weather forecasters in coming decades, said scientists, to tell us how tomorrow will be different from today. Even as Earth's overall temperature -- its climate -- gets warmer and warmer.