11 December 2009CommonDreams

by Sarah van Gelder

Few believe the Copenhagen Summit will result in a deal strong enough to keep climate change within safe limits.

Little wonder. Global warming could be one of the toughest issues the world has ever faced, less because of the technical challenges than the politics. That's why the growing climate movement that has assembled alongside the official delegations in Copenhagen is so important to watch — its success could determine if world leaders feel enough heat to take action.

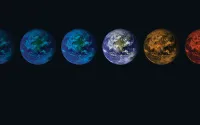

What makes the politics of this moment so challenging? Unlike other critical issues, combating climate change requires that we take action based on science, before we see much damage. If we wait until the effects of long-term pollution are fully felt, climate scientists tell us, we will have passed critical thresholds that will make it difficult, if not impossible, to turn down the global thermostat. Already, we can see the beginnings of the effects of greenhouse gas pollution, but all the models tells us that these will accelerate with more flooding, rising seas, crop failures, food shortages and drought conditions like those of the dust bowl era.

Although many of these changes are happening faster than expected, it's not too late. Climate scientists say we can yet avert the direst consequences if we halt the increase in pollution by 2015, then bring it down sharply. That means taking action now.

Yet, politicians worldwide have short-term reasons to pass this hot-potato issue off to future generations. After all, "cheap" coal-fired electricity concentrates high profits in the hands of a few companies — who hire high-powered lobbyists and make big campaign contribution — while the costs of climate damage is distributed to all the rest of us.

And dealing with the crisis requires massive investments in a transition to clean energy. While such investments will benefit economies in the long run, in the short term they will cost taxpayers money. And entrenched, powerful interests — from the oil and gas industry to mega-banks and agribusiness — use their money and connections to make sure they're at the front of the line for government handouts and bailouts. Some are even funding the think tanks and AstroTurf front groups that foster confusion and doubt about climate science.

In poorer countries, citizens demand the right to move out of poverty. If the wealthier countries that have grown rich from years of polluting use of fossil fuels won't step up, they won't allow their governments to make tough sacrifices either.

Although every community, every nation and every family stands to lose without action on global warming, the political leaders gathered in Copenhagen to negotiate a climate treaty haven't felt heat from their own citizens — at least not yet.

The good news is that around the world there are climate heroes, those doing what they can — putting up solar panels, standing in the way of tar sands development, promoting green jobs, cutting their own household carbon footprints and promoting wind power instead of mountaintop removal. And they are applying pressure for broader action.

Young people, for instance, are mobilizing themselves into a powerful force for change, calling themselves a "survival" movement. Don't underestimate these youths. Their energy and hard work helped elect our country's first African-American president.

But it isn't only the youth who are stepping up. People in all sectors of society are coming to see that action is needed. Four thousand citizens in 38 countries around the world gathered recently to consider in depth all sides of the climate issue and what should be done about it. At the end, nine out of ten urged urgent action out of the Copenhagen talks.

Elected officials can't get the job done unless they feel the heat at home. That puts a special responsibility on Americans to see through the spin, inform ourselves, and take action. The world is waiting for leadership from the United States, the country with one of the highest rates of greenhouse gas pollution. The future of our planet may hinge on whether "we the sovereign people" of the United States insist that our leaders step up to this global threat and partner with the rest of the world to arrive at an agreement that keeps the disruption of our climate within safe limits.Sarah van Gelder is YES! Magazine co-founder and executive editor