11 November 2005The Cape CodderRich Eldred

How long can one ponder the complexities of salty water? A lifetime, according to physical oceanographer Ruth Curry.

"I've been here 25 years measuring the ocean. What I've done is compile all the measurements ever made globally and I'm looking at what's happening with salinity. I imagine I'll spend the rest of my days doing that," she reflected from her cozy office at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Much of that time was spent writing software to analyze every bit of salinity data she could collect. But she's also journeyed far from her Falmouth office.

"I've been everywhere," Curry said. "I've been to almost all the seas, off Greenland, Iceland, Norway."

The conveyor belt is Curry's great concern. The wind-driven Gulf Stream carries warm water across the Atlantic toward England, and is tugged further north by the cooling heavier saltier arctic water that sinks to the bottom and flows south, more or less beneath the Gulf Stream. This both moderates the northern climate and cools the southern skies.

But freshwater is less dense than salty seawater and won't sink to the bottom as fast, which could slow the cold current flowing south, that would in turn slow the entire cycle. And Curry's recent work documents a huge jump in the amount of freshwater pouring into the Arctic seas.

"I've looked at how much freshwater has been added to the North Atlantic and it's an extra 20,000 cubic kilometers since 1970," she said.

She calculated that by looking at the change in salinity and asking how much freshwater was needed to account for that change, she then worked it out backward. About 75 percent of that extra freshwater came from melting polar ice. The rest is due to increased river flow and precipitation.

"Global warming is ongoing and it's just ramping up so it's important to be out there monitoring what its impacts are," Curry declared. "Extra freshwater continues to be dumped into the North Atlantic and will explode in the 21st century as global warming continues."

Global warming is here

Curry is not someone who considers global warming to be a questionable phenomenon.

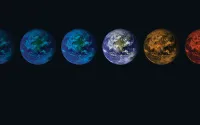

"There's no doubt our planet is warming in this century and the pace of that warming has accelerated," she pointed out. "There's a pretty clear line of evidence accumulating that greenhouse gases like CO2 and methane are responsible."

And she's not basing that on her own measurements at Station W.

"We have more than 100 years of actual surface temperatures from the Civil War to the present and the temperature is rising on average," Curry said. "It's gone up about 1 degree centigrade since 1860. That doesn't sound like much, but that's what we humans would feel in the atmosphere and 1 degree centigrade is actually a huge amount of heat energy. So the earth's energy budget is changing."

She's nothing if not passionate and wasn't shy about identifying a culprit.

"We have changed the amount of heat bounced out to space," Curry said. "We have from ice cores what the CO2 was back half a million years. For the last 4,000 years the CO2 fluctuated between 190-290 parts per million. Right now we're at 379 ppm. That's an all time high. One source of that is burning fossil fuels."

While most folks focus on the air temperature, noting for instance that this was the warmest September in 111 years, Curry looks at the sea.

"Most of this extra energy the Earth has retained has gone into the ocean because water is a more efficient heat sink than the air is. The ocean has absorbed 20 times more heat than the atmosphere and land," she noted.

This has led to changing rain patterns: North America has gotten drier, Central Asia and the Arctic, wetter. Asia is pouring much of that extra freshwater into the Arctic.

"Since 1997 we've had seven of the warmest years ever recorded," Curry noted.

That's increased ocean evaporation in the low latitudes, making southern seas more salty, as the slat is left behind. The warm temperatures have also boosted the melting of polar ice and glaciers, turning the Arctic seas less saline. Curry has documented this trend over the past 50 years.

"Precipitation is increasing in the (Arctic) and river discharge in the Arctic Ocean is increasing and the Arctic sea ice is shrinking," Curry said. "Greenland's land-based glaciers are melting. That's a recent development. Greenland stores enough water to raise sea levels by 20 feet."

Warmer on the Cape?