Common Dreams / Published on Thursday, August 23, 2007 by The San Francisco ChronicleSam Zuckerman

Steven Bustin lives with his wife in a four-bedroom, 2,600-square-foot house in Novato. He drives a gray 2006 Audi A4. He earns more than $200,000 a year in salary and commissions from his job as head of sales for Podaddies, an Internet startup that sells online video ads.

Tamara Johnson lives with her three children in a two-bedroom apartment in the Sunnydale housing project in San Francisco’s Visitacion Valley. She drives a used 2003 Buick Sebring with 74,000 miles on it. Last year, she brought in just under $12,000 from her job as a home health care worker, supplemented by disability payments for two of her kids.

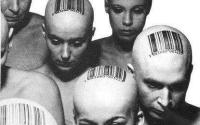

Bustin and Johnson represent California’s increasingly polarized economy.

The gap between the state’s rich and its poor is getting bigger. The bulk of job growth in California over the last generation took place at the top or bottom of the pay scale, a trend that has accelerated since the beginning of this decade. Jobs in the middle are scarcely growing at all.

The changes are documented in a report based on census and tax data set for release today by the California Budget Project, a liberal research and advocacy group.

“The story of the past generation is one of widening income inequality,” the group says about the state.

It’s well documented that the gulf between highly paid and low paid people is growing across the country. But it is more pronounced in California, according to census and tax records.

The divisions suggest that poverty will persist despite California’s growing economy. And the erosion of middle-income jobs could make the American dream of climbing the economic ladder harder to achieve in the state, the budget project warned.

“You’re in essence taking steps out of the ladder,” said Jean Ross, the group’s executive director. “These are troubling signs for our society.”

The growing disparity between the wanting and the well-to-do shows up starkly in pay data.

Since 1979, 26.9 percent of new positions created in California were in such categories as food service and retail trade, which paid hourly wages in the bottom fifth of all jobs, the report finds. At the other end of the spectrum, 28.1 percent of new jobs were in such categories as administration and management, which paid in the top fifth.

The breach has expanded this decade. From 1999 to 2005, 43.1 percent of California’s job growth occurred among jobs at the lowest 20 percent of the pay scale. About 54.4 percent of new jobs were in the top 40 percent of pay. Only 2.6 percent of growth came among jobs at 20 to 60 percent of the pay scale.

“We’re having a hollowing-out of job growth,” Ross said.

As a result, California’s population is polarizing. A large group at the top enjoys a standard of living significantly higher than it did three decades ago. Another large group is living worse. A shrinking fraction of people in the middle is getting squeezed, according to the budget group’s study.

From 1979 to 2006, the hourly pay of California’s low-wage workers fell by 7.2 percent after adjusting for inflation. High-wage workers saw gains of 18.4 percent, while those exactly in the middle edged up 1.3 percent. The richest Californians are capturing a growing share of wealth. Income reported for tax purposes of the top 1 percent of the state’s taxpayers jumped 107.7 percent from 1995 to 2005, after adjusting for inflation. During the same period, income of the middle fifth of taxpayers rose 9.3 percent. California households are losing ground compared with their counterparts elsewhere. A California household in the middle of the scale saw inflation-adjusted income from wages, investments and other sources grow 3.1 percent between 1989 and 2005. Nationwide, income for a typical household rose 5.4 percent.Jobs are growing at the top and bottom for many reasons. But those factors can be summed up in a word - globalization. California lost 464,700 manufacturing jobs - many of them paying middle-class wages - between 1990 and 2006, much of that work moving overseas.

Meanwhile, the service sector boomed. The category includes low-paid jobs, such as retail clerks, and well-paid jobs, such as lawyers and accountants. The California employee head count of Walgreens, the rapidly expanding drug store chain, surged to 14,900 in August 2007 from 8,000 five years before, a company spokeswoman said.

Other trends are intensifying the income gap. California has lots of immigrants willing to accept low-wage jobs. Fewer of the state’s workers belong to trade unions, which historically have given workers bargaining power.

An increasing proportion of the nation’s income is going to corporations, which benefits households that invest in stocks and bonds. And federal policies have reduced the tax burden on upper-income households.

Education is the main factor separating winners and losers. From 1979 to 2006, California workers with bachelor’s degrees saw real wage gains of 19.8 percent. Wages of workers with master’s degrees or higher jumped 34.4 percent. But high school graduates’ wages fell 4.4 percent after adjusting for inflation, while the wages of those who did not graduate high school plunged 23.7 percent.

Some experts believe California is losing middle-income jobs because of the high cost of doing business and public policies that drive employers out of the state.

Many of the state’s middle-income manufacturing and service-sector jobs have moved to states such as Arizona and Texas, where wages are lower and government policies friendlier to business, said Joel Kotkin, an expert on California’s cities and a presidential fellow at Chapman University in Orange.

The budget project’s report “didn’t deal with infrastructure, didn’t deal with competitiveness,” Kotkin said. “You have to look at tax climate and regulatory climate. Business climate matters in terms of job creation.”

Of course, Steven Bustin and Tamara Johnson aren’t bits of data, nor do they want to be poster children for California’s rich and poor. Neither fits stereotypes of suburban affluence or inner-city poverty. Still, both live lives that are, to a very considerable degree, reflections of the means they have at hand.

Bustin, 55, doesn’t have a particularly lavish lifestyle. He and his wife, Gigi, give several thousand dollars each year to Catholic charities and other causes. He recently wrote a book about the cruiser on which his father served during World War II. He and Gigi prefer kayaking in San Francisco bay to a weekend in a fancy hotel.

“We are mindful of the budget,” Bustin, a native of Baltimore, said.

Still, they have the income for luxuries, such as a vacation last year in Hawaii’s Big Island and the occasional dinner at fancy restaurants. San Francisco’s pricy Boulevard is a favorite.

Johnson, 35, who grew up in Berkeley, doesn’t have many choices. She is raising an 8-year-old son and 9- and 15-year-old daughters in crime-ridden public housing, where $744 in monthly rent eats up most of her paycheck. She does the best she can for her kids, taking them to parks and the zoo on weekends. Her oldest daughter has developed a passion for all things Japanese, so the city’s Asian Art Museum is a frequent destination.

She has considered a move to the Dublin area or even to Sacramento, safer environments than Sunnydale, but can’t find the time to make arrangements.

Her life “is very difficult,” she said. “I have to squeeze, squeeze, squeeze every penny. And there’s no resources.”

What to do about California’s income gap

How to address growing economic inequality in California is hotly disputed, based on politics and ideology.Here are two views:

JEAN ROSS

Jean Ross, executive director of the California Budget Project, a liberal advocacy group, argues that it’s futile to try to stop globalization by backing protectionist measures. Instead, she favors “public policies that soften the impact of the market.” These include tying the minimum wage to inflation, extending health coverage to all Californians and making sure schools turn out well-trained workers.

JOEL KOTKIN

Author and scholar Joel Kotkin, often linked with conservatives but who describes himself as a “Pat Brown Democrat,” contends California must work to retain middle-class jobs by improving its business climate. He calls for better maintenance of the state’s infrastructure and for review of business regulations and tax policy.

Sources: California Budget Project and Joel Kotkin