March 2005 issueScientific American.comDavid Appell

Michael Mann knows his students and his subject. The topic of the graduate seminar: El Niño and radiative forcing. The beer he will be serving: Corona, "because I'm going to be talking about tropical climate." Not surprisingly, attendance is high.

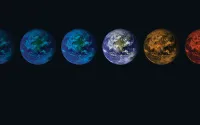

Mann is most famously known for the "hockey stick," a plot of the past millennium's temperature that shows the drastic influence of humans in the 20th century. Specifically, temperature remains essentially flat until about 1900, then shoots up, like the upturned blade of a hockey stick. The work was also the first to add error bars to the historical temperatures and allow for regional reconstructions of temperature.

That stick has become a focal point in the controversy surrounding climate change and what to do about it. Proponents see it as a clear indicator that humans are warming the globe; skeptics argue that the climate is undergoing a natural fluctuation not unlike those in eras past. But Mann has not been deterred by the attacks. "If we allowed that sort of thing to stop us from progressing in science, that would be a very frightening world," says the 39-year-old climatologist in his University of Virginia office overlooking the hills of Monticello, the home of Thomas Jefferson.

Mann thinks that the attacks will continue, because many skeptics, such as the Greening Earth Society and the Tech Central Station Web site, obtain funds from petroleum interests. "As long as they think it works and they've got unlimited money to perpetuate their disinformation campaign," Mann believes, "I imagine it will go on, just as it went on for years and years with tobacco until it was no longer tenable--in fact, it became perjurable to get up in a public forum and claim that there was no science" behind the health hazards of smoking.

As part of his hockey-stick defense, Mann co-founded with Schmidt a Weblog called RealClimate (www.realclimate.org). Started in December 2004, the site has nine active scientists, who have attracted the attention of the blog cognoscenti for their writings, including critiques of Michael Crichton's State of Fear, a novel that uses charts and references to argue against anthropogenic warming. The blog is not a bypass of the ordinary channels of scientific communication, Mann explains, but "a resource where the public can go to see what actual scientists working in the field have to say about the latest issues."

The most challenging aspect today, Mann thinks, is predicting regional disruptions, because people are unlikely to take climate change seriously until they see how it operates in their backyard. In that regard, he has turned his attention to El Niño, a warming of eastern tropical Pacific waters that affects global weather. In discussing the issue with his students over their Coronas, Mann notes that comparisons with the paleoclimatic record seem to confirm a mechanism proposed by other researchers. Specifically, radiative forcings--volcanic eruptions and solar changes, for instance--do in fact alter El Niño, turning it into more of a La Niña state, with colder sea-surface temperatures. Understanding how El Niño has changed with past radiative forcings is a first step to understanding how it will change in an increasingly greenhouse-gassed world.

Mann remains somewhat mum on whether the U.S. should join the Kyoto Treaty, an international agreement to limit fossil-fuel emissions: "It's hard enough predicting the climate. I don't pretend to be able to predict the behavior of politicians." He sees the Kyoto accord as an initial step that is unlikely to curtail emissions all that much, but it will at least set in motion a process that can be built on with other treaties. Such efforts are essential, because the blade of Mann's hockey stick will get longer. He notes that "we're already committed to 50 to 100 years of warming and several centuries of sea-level rise, simply from the amount of greenhouse gases we've already put in the atmosphere." The solution to global warming, he observes, "is going to be finding an appropriate set of constraints on fossil-fuel emissions that allow us to slow the rate of change down to a level we can adapt to."