2 July 2008The Progressive

(In memory of George Carlin.)

It's July 4th again, a day of near-compulsory flag-waving and nation-worshipping. Count me out.

Spare me the puerile parades.

Don't play that martial music, white boy.

And don't befoul nature's sky with your F-16s.

You see, I don't believe in patriotism.

It's not that I'm anti-American, but I am anti-patriotic.

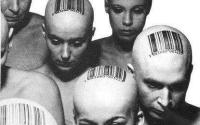

Love of country isn't natural. It's not something you're born with. It's an inculcated kind of love, something that is foisted upon you in the home, in the school, on TV, at church, during the football game.

Yet most people accept it without inspection.

Why?

For when you stop to think about it, patriotism (especially in its malignant morph, nationalism) has done more to stack the corpses millions high in the last 300 years than any other factor, including the prodigious slayer, religion.

The victims of colonialism, from the Congo to the Philippines, fell at nationalism's bayonet point.

World War I filled the graves with the most foolish nationalism. And Hitler and Mussolini and Imperial Japan brought nationalism to new nadirs. The flags next to the tombstones are but signed confessions—notes left by the killer after the fact.

The millions of victims of Stalin and Mao and Pol Pot have on their death certificates a dual diagnosis: yes communism, but also that other ism, nationalism.

The whole world almost got destroyed because of nationalism during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The bloody battles in Serbia and Bosnia and Croatia in the 1990s fed off the injured pride of competing patriotisms and all their nourished grievances.

In the last five years in Iraq, tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of Iraqi civilians have died because the United States, the patriarch of patriotism, saw fit to impose itself, without just cause, on another country. But the excuse was patriotism, wrapped in Bush's brand of messianic militarism: that we, the great Americans, have a duty to deliver "God's gift of freedom" to every corner of the world.

And the Congress swallowed it, and much of the American public swallowed it, because they've been fed a steady diet of this swill.

What is patriotism but "the narcissism of petty differences"? That's Freud's term, describing the disorder that compels one group to feel superior to another.

Then there's a little multiplication problem: Can every country be the greatest country in the world?

This belief system magically transforms an accident of birth into some kind of blue ribbon.

"It's a great country," said the old Quaker essayist Milton Mayer. "They're all great countries."

At times, the appeal to patriotism may be necessary, as when harnessing the group to protect against a larger threat (Hitler) or to overthrow an oppressor (as in the anti-colonial struggles in the Third World).

But it is always a dangerous toxin to play with, and it ought to be shelved with cross and bones on the label except in these most extreme circumstances.

In an article called "Patriot Games" in the current issue of Time magazine (July 7), Peter Beinart, late of The New Republic, inspects his navel for seven pages and then throws the lint all around.

"Conservatives are right," he says. "To some degree, patriotism must mean loving your country for the same reason you love your family: simply because it is yours."

And then he criticizes, incoherently, the conservative love-it-or-leave-it types.

The moral folly of his argument he himself exposes: "If liberals love America purely because it embodies ideals like liberty, justice, and equality, why shouldn't they love Canada—which from a liberal perspective often goes further toward realizing those principles—even more? And what do liberals do," he asks, "when those universal ideals collide with America's self-interest? Giving away the federal budget to Africa would probably increase the net sum of justice and equality on the planet, after all. But it would harm Americans and thus be unpatriotic."

This is a straw man if I ever I saw one, but if the United States gave a lot more of its budget to eradicating poverty and disease in Africa and other parts of the developing world, it might actually make us all safer.

At bottom, note how readily Beinart disposes of "liberty, justice, and equality."

He has stripped patriotism to its vacuous essence: Love your country because it's yours.

If we stopped that arm from reflexively saluting and concerned ourselves more with "universal ideals" than with parochial ones, we'd be a lot better off.

We wouldn't be in Iraq, we wouldn't have besmirched ourselves at Guantanamo, we wouldn't be acting like some Argentinean junta that wages illegal wars and tortures people and disappears them into secret dungeons.

Love of country is a form of idolatry.

Listen, if you would, to the wisdom of Milton Mayer, writing back in 1962 a rebuke to JFK for his much-celebrated line: "Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country."

Mayer would have none of it. "When Mr. Kennedy spoke those words at his inaugural, I knew that I was at odds with a society which did not immediately rebel against them," he wrote. "They are the words of totalitarianism pure; no Jefferson could have spoken them, and no Khrushchev could have spoken them better. Could a man say what Mr. Kennedy said and also say that the difference between us and them is that they believe that man exists for the State and we believe that the State exists for man? He couldn't, but he did. And in doing so, he read me out of society."

When Americans retort that this is still the greatest country in the world, I have to ask why.

Are we the greatest country because we have 10,000 nuclear weapons?

No, that just makes us enormously powerful, with the capacity to destroy the Earth itself.

Are we the greatest country because we have soldiers stationed in more than 120 countries?

No, that just makes us an empire, like the empires of old, only more so.

Are we the greatest country because we are one-twentieth of the world's population but we consume one-quarter of its resources?

No, that just must makes us a greedy and wasteful nation.

Are we the greatest country because the top 1 percent of Americans hoards 34 percent of the nation's wealth, more than everyone in the bottom 90 percent combined?

No, that just makes us a vastly unequal nation.

Are we the greatest country because corporations are treated as real, live human beings with rights?

No, that just enshrines a plutocracy in this country.

Are we the greatest country because we take the best care of our people's basic needs?

No, actually we don't. We're far down the list on health care and infant mortality and parental leave and sick leave and quality of life.

So what exactly are we talking about here?

To the extent that we're a great (not the greatest, mind you: that's a fool's game) country, we're less of a great country today.

Because those things that truly made us great—the system of checks and balances, the enshrinement of our individual rights and liberties—have all been systematically assaulted by Bush and Cheney.

From the Patriot Act to the Military Commissions Act to the new FISA Act, and all the signing statements in between, we are less great today.

From Abu Ghraib and Bagram Air Force Base and Guantanamo, we are less great today.

From National Security Presidential Directive 51 (giving the Executive responsibility for ensuring constitutional government in an emergency) to National Security Presidential Directive 59 (expanding the collection of our biometric data), we are less great today.

From the Joint Terrorism Task Forces to InfraGard and the Terrorist Liaison Officers, we are less great today.

Admit it. We don't have a lot to brag about today.

It is time, it is long past time, to get over the American superiority complex.

It is time, it is long past time, to put patriotism back on the shelf—out of the reach of children and madmen.